Cycling for peace, running for freedom

Racing through the Velvet Revolution

“A healthy mind in a healthy body” was the motto of the Soviet people in the 1930s. In the following years, sport has always played a key role in the propaganda of the communist regime. The subsequent dissolution of the Czechoslovak communist state changed its meaning. On November 17th, a group of young Czech people ran through their country to honour what made this shift possible: the Velvet Revolution.

Sports under Communism

The labyrinthine hallways of Strahov Stadium in Prague have witnessed some of the most significant sports and propaganda events in history. Between 1955 and 1989, the stadium served as a stage for nationalist gymnastic festivals. These performances were not merely a demonstration of physical strength, but they were also used as a tool to convey a message of national unity and the power of the socialist state.

Czech sports journalist Darina Vymětalíková, who has a PhD in media studies, looking at the connection between sports and ideology between 1945-1952, said,

“Let’s say in our liberal society. There are huge differences between the connection of the state in the free world. Usually, the state doesn't have too much power to organise sports or to spread propaganda. In the Nazi era or the communist era, it was the main purpose of the sport.”

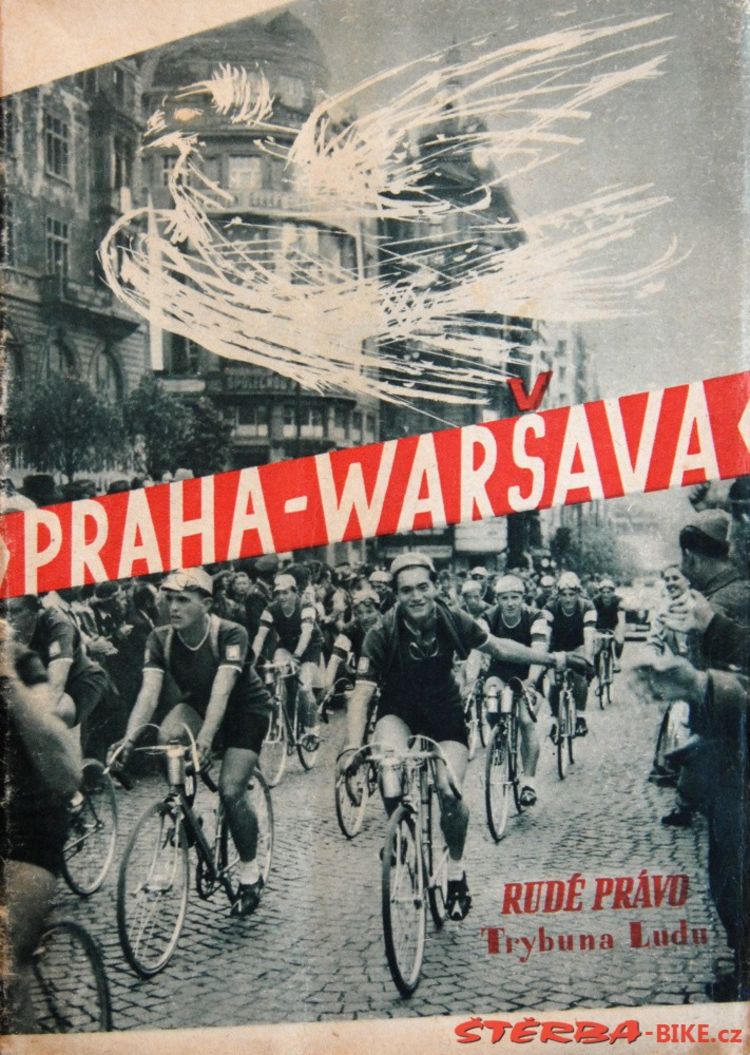

Štěrba-Bike. (n.d.). Peace Race – “Course de la Paix”. Štěrba-Bike.cz.

Štěrba-Bike. (n.d.). Peace Race – “Course de la Paix”. Štěrba-Bike.cz.

Štěrba-Bike. (n.d.). Peace Race – “Course de la Paix”. Štěrba-Bike.cz.

Štěrba-Bike. (n.d.). Peace Race – “Course de la Paix”. Štěrba-Bike.cz.

Závod míru

In the late 1940s, the Peace Race was created by members of the press from communist parties, along with cycling federations from Poland and Czechoslovakia. The event lasted from 1948 to 2006, and it was funded on a core idea: building bridges between bikers from their respective nations. The first Peace Race consisted of two separate races: from Warsaw to Prague and from Prague to Warsaw. Almost one hundred amateur athletes from Poland, Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, Romania, and Hungary were invited to hop on their bikes to promote unity within the Eastern Bloc.

Socialists used the event to emphasise concepts such as brotherhood among nations, friendship, and peace. In contrast to more well-known events, such as the Tour de France or the Giro d’Italia, the Peace Race was open to amateurs. This fact was largely used by the propaganda machine to highlight how Western Europe distorted the real meaning of sport and transformed it into something useful exclusively to gain profit.

Vymětalíková said that when a Czech cycling magazine covered the race in 1950, the majority of the pages in that edition were not about the race.

“14 or 16 pages were about this political stuff, and nobody knows who won,” she said. “So it was a paradox. It was so funny that you can read what politicians from all the towns and cities along the race were thinking about fighting the bad Western world. But there was no writing who won, who was second.”

On the other hand, the decision to open the competition to all-level athletes gave socialists the opportunity to portray themselves as genuine sports enthusiasts, regardless of their professional abilities.

Over time, the race became increasingly successful. In a few years, it become a huge event, attracting crowds in every town that the cyclists visited. The popularity was such that it was decided to organise the final stages of the race in massive stadiums, where people from every country could come and admire the "achievement of socialism”.

The race gained significant prestige and inevitably became an ideological battlefield due to the escalating tensions of the Cold War. When Western athletes or teams competed, they were usually from workers’ cycling clubs, so “everything was okay” ideologically, said Vymětalíková.

The ideological context behind the Peace Race was never a secret, "it was praise for peace, international friendship, and socialism."

Racing through the revolution

Nowadays, while sport is not controlled by the mechanisms of the state, it is still political.

“Sport is the space for people. And every space that is occupied by people is also occupied by ideology," said Vymětalíková.

When asked about “Run Through the Heart of the Republic,” she said that today there are more commemorations of November 17th, whether in sports or otherwise, than there were in the years immediately following the Velvet Revolution, possibly because the Czech Republic is “more divided now.”

She said that for some people, it is important to show which side of society they are on, perhaps through sporting events or theatre, or concerts.

“These events are much more visible, or there are a lot of there are more of these events now, because people somehow think that our independence may be threatened. It's connected with the war in Ukraine and with Russia. So, yes, a lot of people voluntarily connect politics or ethics and sports right now.”

From the 15th to the 17th of November, SideQuesty, an organisation dedicated to “sidequests” and getting people outside to adventure, organised a run from Brno to Prague to remember and honour those events that led to democracy in the Czech Republic.

SideQuesty runners passing through Karlín.

SideQuesty runners passing through Karlín.

“This day is super important for us, as this is the 17th November celebration of the Velvet Revolution, where the students fought against communism in the Czech Republic," said SideQuesty co-founder Stanislav Štěpánek. "Young people who faced their fears were actually able to overcome the regime and overthrow it. So we believe that it's super important for the new wave to keep moving,”

The symbol of the race was two flags: one for the Czech Republic and a white flag, on which people had the opportunity to sign and carry throughout the entire journey. The flag passed from hand to hand among the different runners every time they entered a new section, and it finally reached the capital on Monday, the 17th, where the group gathered to celebrate the Velvet Revolution.

“It was a two-day run. It was really hard. It was raining, and the rain was so powerful that people had to meet to exchange flags. So it was really about connection, about the community itself, and about the freedom that we have, that we can run, and we can run through the cities, and we are able to do this," said another SideQuesty co-founder, Ema Urbánková. “It was really powerful, because the message was that we have a flag, and the flag travelled through the cities from Brno to Praha, without a break."

SideQuesty in the final stretch of their race, where student protesters in 1939 & 1989 protested for freedom.

SideQuesty in the final stretch of their race, where student protesters in 1939 & 1989 protested for freedom.

Náměstí Svobody - translated to “Freedom Square” in English and the sight of demonstrations on Nov. 20th, 1989, inspired by the events earlier in Prague, four minutes from where ‘Run Through the Heart of the Republic’ began.

Astronomical Clock: The Nazi Germany army, while being driven out by the Soviets shot at this city’s astronomical clock, leaving only a few pieces intact. Under communism, it was rebuilt, showcasing ‘proletarians’ instead of saints.

Home of the Bata shoe company, 2004 World Record Holder for Largest Shoe Company. Nationalized after WWII without compensation.

Zámečeck Memorial, which honours the 194 people who were executed there by the Nazis in 1942. It is one of several memorials and monuments along the race’s path that honour victims of WWI and WWII.

Capitol of the Czech Republic and a central location for both the Peace Race, from beginning to end, and the first Run Through the Heart of the Republic

In contrast to the Peace Race, this race was less well known and less attended, but the dedication to run 432 kilometres in under 48 hours was immensely meaningful to the runners.

Štěpánek said under communism, people had to choose between “what they liked” and representing their “political beliefs” because to participate in organised sport, one had to be associated with the communist party.

77 years since the first Peace Race, two symbolic flags ran across the country, depicting a country that has fought to gain its independence and is aware of the costs that the journey, or race, to democracy needs.

“We run for freedom. We run because we can not, because someone told us that we have to do it" said Urbánková.

An interview with Štěpánek (Left) and Urbánková (Right) after the finish of the first Run Through the Heart of the Republic.

An interview with Štěpánek (Left) and Urbánková (Right) after the finish of the first Run Through the Heart of the Republic.

“Fight for freedom and fight for freedom of speech. I think it's really important that we talk about it. Don't be afraid. Just talk about it with anyone you can, like, with your grandma, with your grandpa, with your sister. Just talk about it.”

Ema Urbánková

This multi-media project was an assignment in a "Post-Digital Photojournalism" class at FSV Charles University looking into the Velvet Revolution and how it is commemorated today.

Lorea (USA), Asmaa (Spain), Laura (Italy), and Bori (Hungary) are masters students in the EMJ Journalism program and Gréta (Hungary) is studying for a MA in social work and community development.